- Author

- Ana Prendes

Ahead of their residency at the Laboratory, we spoke to the artists about their ambition to develop solar balloons that rest on clouds, their lifelong dedication to observing the colour of the sky, and their perspectives on the role of art in the climate crisis

Since 2003, Hemauer and Keller’s artistic research has demonstrated a profound ecological and political commitment, expressed through films, installations, performances, and publications. A central focus of their work is the history of oil and its alternatives, particularly solar energy. In recent years, they have turned their attention to exploring the evolving human-nature relationship in the age of the climate crisis.

One significant area of their research investigates changes in the blueness of the sky caused by global heating and geopolitical decisions. In 2015, they recreated Horace-Bénédict de Saussure’s Cyanometer in their project Concerning the Blueness of the Sky. After consulting climatologist Atsumu Ohmura, they developed solar balloons designed to reach the lower stratosphere, converting the motion picture images into tonal values for their installation Voyages atmosphériques (2016).

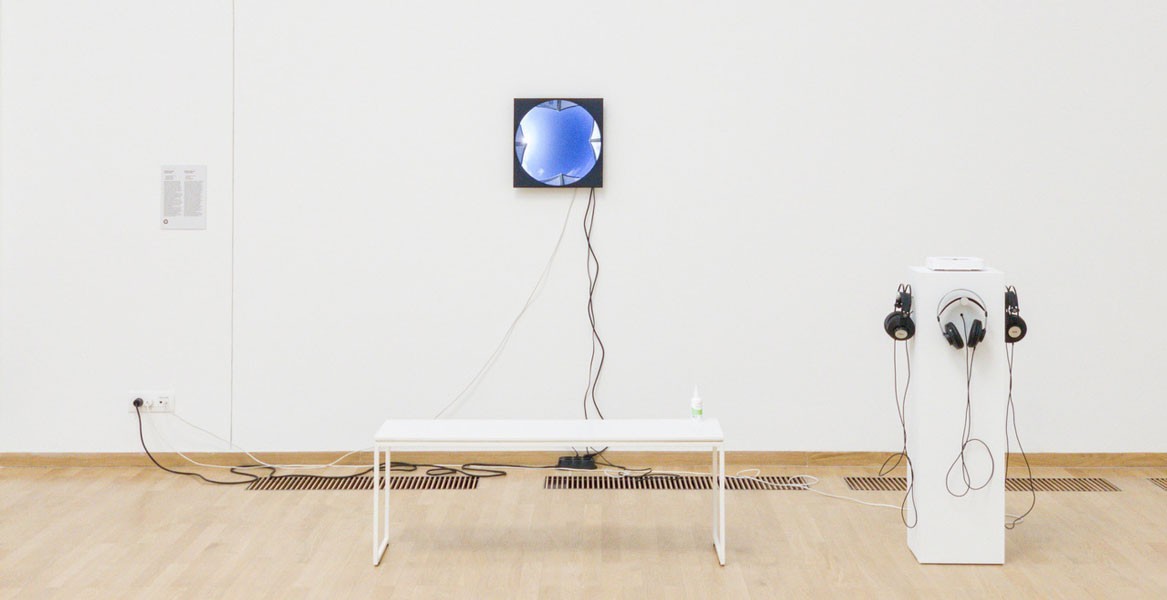

Their most recent project, Observing Human Skies (2021), features an all-sky, self-cleaning camera that captures two images every 30 seconds. Deliberately placed on a museum’s rooftop, the device transforms the ever-changing colours of the sky into part of the museum’s collection.

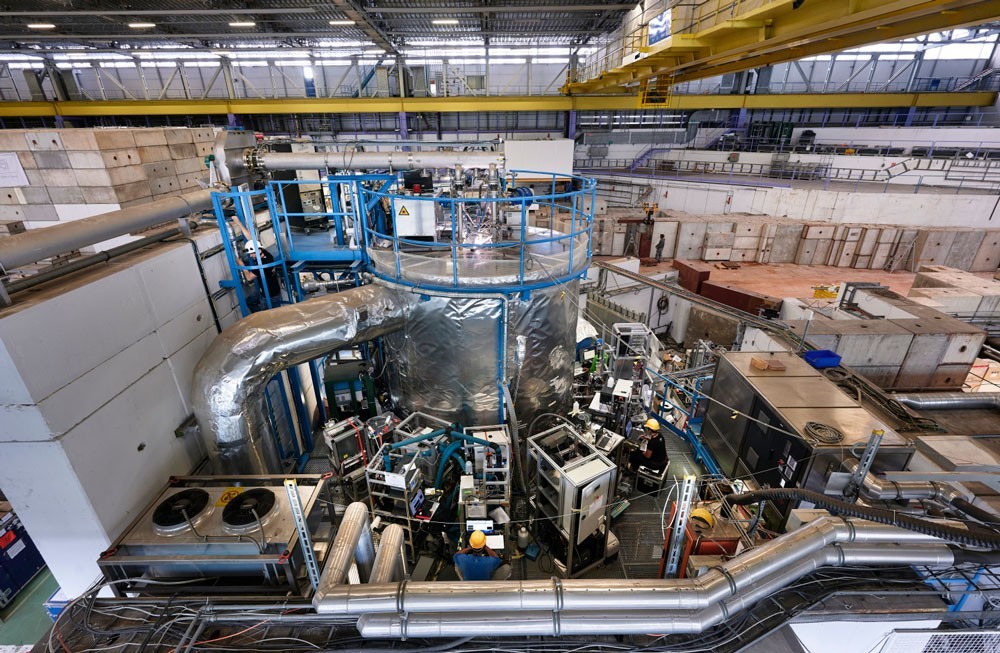

During their residency at CERN, supported by the Swiss Arts Council Pro Helvetia, Hemauer and Keller plan to continue this research in collaboration with researchers from the CLOUD Experiment, aspiring to observe and measure the colour of the sky for the rest of their lives.

You’ve previously worked with climate scientists studying the effects of the Anthropocene in the sky, but they aren’t concerned with its colour changes. How did your interest in studying the blueness of the sky come about?

We were surprised that the colour of the sky was not scientifically observed. Climate researchers assume that it has already changed and will continue to change in the future. The argument of Reto Knutti, a climatologist at ETH Zurich, affirming that the sky colour is not a relevant scientific value, provoked us. We thought that this is where art has to come into play.

What attracted you in the first place to such a specialised scientific environment like CERN?

When we received the [Collide Pro Helvetia] Award, which we won with a residency project proposing a cooperation with the CLOUD Experiment – we didn’t know what kind of gift we were given. We think the spirit of cooperation is unparalleled to clarify the fundamental questions of our existence. We feel that the employees at CERN sometimes also secretly think: “What we’re doing here is a bit crazy”. Likewise, we know this feeling well as artists – even if our plans and budgets are much more manageable. On the one hand, what is delightful at CERN is the excellence of the scientists and the entire team. On the other hand, it is the influence of their findings on our culture.

The CLOUD Experiment at CERN studies the possible link between galactic cosmic rays and cloud formation. What do you intend to develop during your residency in cooperation with CLOUD researchers?

We suggested developing our solar balloons so that they could float on top of a cloud layer. We like the idea of building something that sits on a cloud itself. The intention is also to be able to include some instruments to find out more about the clouds. We know we will measure cosmic rays with a CERN sensor. The rest is currently under discussion.

In your project Concerning the Blueness of the Sky, you restored the Cyanometer, a 18th-century sky colour measurement device, and in Voyages atmosphériques, you developed solar balloons to measure the blueness of the sky, showing both technical inventiveness and aesthetic approach. How would you describe your work within the more traditional division between artistic and scientific research?

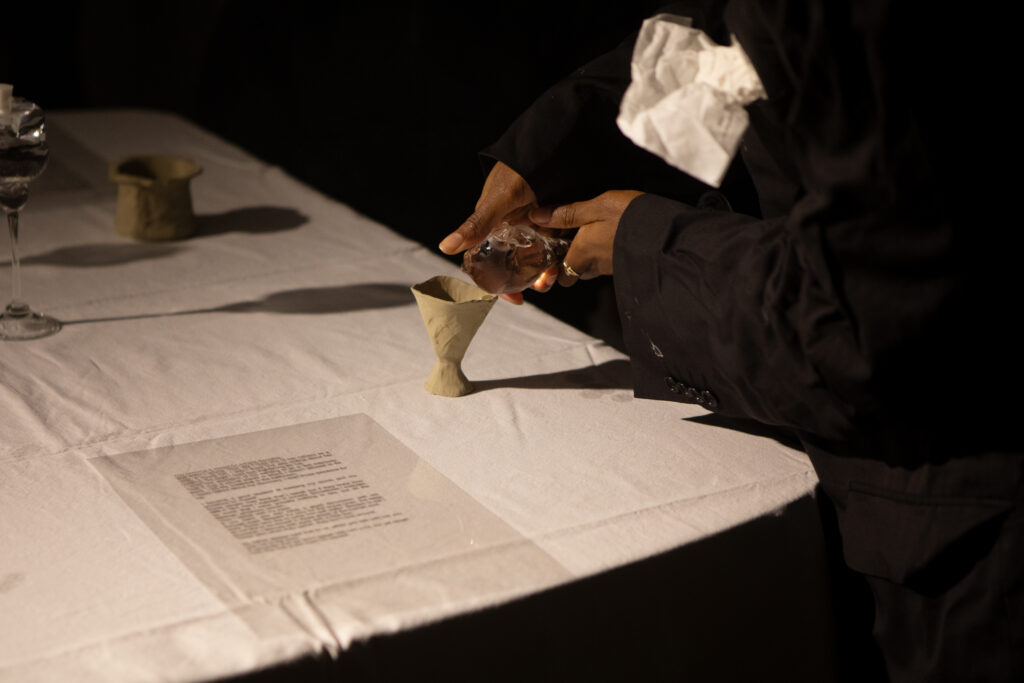

Regarding the Cyanometer, we were interested in making the instrument usable again. The few remaining copies are yellowed and faded. We took Horace-Bénédict de Saussure’s instructions from the end of the 18th century and tried to make the same dilution series with the same pigments, for which we also used modern [measuring] instruments such as a spectrometer. In the art context, there is the practice of re-enactment – a repetition and reappropriation of already existing things. In a scientific context, it would rather be understood as a historical experiment. Although the procedures are similar, a scientific paper would be produced in a scientific context. For us, it’s about the sensory experience of being able to use the Cyanometer again.

Concerning the solar balloons, we were fascinated by the possibility of visiting the place where the blue of the sky is created. In the lower stratosphere at the height of 17 km, 90% of the atmosphere is left below. If you look up from there, the sky is black. The atmosphere, where the incoming sunlight is scattered and the sky is made blue, is only a thin breath that snuggles up the Earth.

Can you share more about your project Observing Human Skies (2021)? Why is it situated on a museum’s roof?

It is a classic task of art museums to collect human-made objects. We would like to build a bridge between museums and science with a series of data from sky images taken at least during 30 years. In the Museum of Contemporary Art Belgrade, we installed the first prototype of a two-lens, self-cleaning all-sky camera with a 180° fish-eye lens, which takes two pictures every minute, and will do it over 100 days. The images are converted into a 1.2-minute film overnight and then looped on a monitor in the exhibition with all the videos from previous days. The aim is to obtain data good and valuable enough, so it can also be used scientifically. We are in contact with various scientists to achieve it.

You seek to observe the colour of the sky for the next 30 years, as following the sky involves bearing witness to the impact of human activities. How has your research evolved with the worsening of the climate crisis? How do you envision the future of the sky?

In the Middle Ages, we believed in the place of God in heaven. Today, we have to admit that we ourselves have a part in shaping the sky. Like all the changes occurring because of climate change, it scares us. At the same time, we have no choice but to take responsibility for what we do. Concerning the sky, the colour could change in either direction. With a reduction in the emissions of soot particles produced by burning fossil fuels, the sky would get bluer. This has already happened in Western Europe and North America with the introduction of catalytic converters; the phenomenon is called Global Brightening.

If, for example, China suddenly switched off its coal-fired power plants, the global climate would warm up by approx. 0.2 °C, as less sunlight would be reflected in the atmosphere. On the other hand, researchers have been thinking for a long time to slow down climate change with the targeted introduction of sulphate particles into the upper atmosphere. In this way, parts of the sunlight will be reflected and its scattering will change1, which would make our skies whiter.

What role does art play in developing new forms of understanding the climate crisis and bringing about a paradigm shift to build a post-anthropocentric future?

We assume that a post-anthropocentric age will only arise when humans die out. If not, our species will have to take on even more responsibility for natural cycles and the limited regenerative capacity of the Earth. This requires a profound cultural change. In this process, art can certainly raise a few critical questions and sharpen awareness of things that are not in focus. However, we should not overestimate the role of art. As with fundamental research, art is of partial social interest. Both have always provided essential insights and knowledge, which, however, often only arrive at the mainstream much later. Concerning climate change, they might even arrive too late.