- Tags

- Art commissions, Artistic residencies

- Author

- Ana Prendes

The Mexican artist, a recipient of an Honorary Mention of the Collide Award, reflects on her interest in early technologies, storytelling, and drawing connections between Indigenous knowledges and fundamental physics

In your Collide proposal Quantum Fictions, you aim to interweave connections between ‘Indigenous Knowledge (considering the wide diversity of tribes) and Western Science.’ Where do these two ways of thinking overlap

Indigenous perspectives are holistic, grounded in interconnectedness, reciprocity, and deep respect for nature. Throughout history, Indigenous peoples have developed many technologies and contributed significantly to science. However, much of this knowledge has been lost. The rejection of magical thinking and natural wisdom has caused considerable damage. Although the value of integrating Indigenous science with Western science is now recognized, we have barely scratched the surface of its potential.

Both Western and Indigenous Knowledge share several fundamental attributes as ways of knowing. Both rely on repetition and verification, inference and prediction, empirical observations, and the recognition of patterns. Science is the pursuit of knowledge, but the approaches to gathering that knowledge are culturally relative. Indigenous science incorporates traditional knowledge and Indigenous perspectives, while non-Indigenous scientific approaches are commonly recognized as Western science. Together, they contribute significantly to modern science.

In the search for answers to fundamental questions about the more-than-human history of the cosmos, particle physics has scrutinized the world at the quantum scale, revealing new knowledge and the extent of our unknowing. At the particle level, matter and energy behave very differently from the reality we perceive in everyday life. The quantum world has its own materiality. At the same time, Indigenous knowledge has, for centuries, offered explanations of these fundamental questions, moving between the real and imaginary, the measurable and immeasurable, the visible and invisible—simultaneously. Quantum entanglement, or non-locality—considered a quintessential quantum effect—has always been integrated into the cosmic vision of Indigenous peoples, though Western cultures have not easily accepted it.

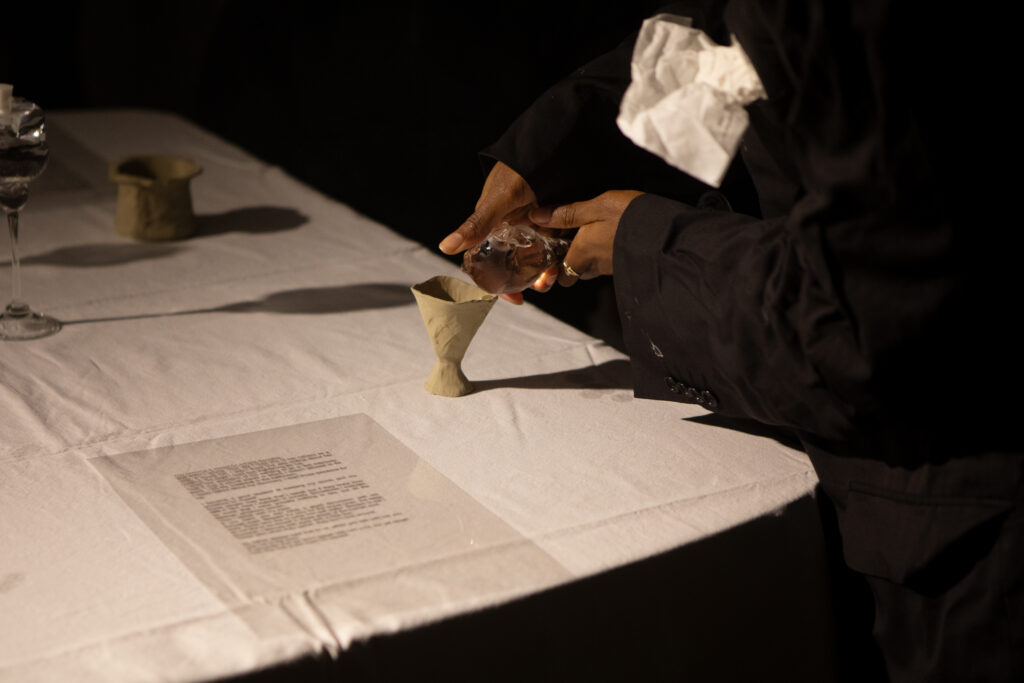

I seek to merge a Western aesthetic canon that privileges vision and metaphysical knowledge and Indigenous oral traditions encoded in the body and ritual

What attracts you to CERN’s scientific environment?

CERN provides a space for cross-disciplinary empathy, enriching perception and cognition through lived experience. I am fascinated by how scientists and artists acquire, process, and respond to information from their environment. I see this space as where the borders between cultures, deep time, and ecosystemic relations are stretched in a delicate but extraordinary interplay.

The association between instruments and language took a new turn with the introduction of recording tools, which began to write results in their own “languages.” These new languages are, in a way, “experimental graphics.” I am interested in exploring new uses for these “graphic traces” and converting the scientists’ narratives into stories and metaphors.

Are philosophical instruments more like words, like things, or somewhere in between? Establish the symbolic character of instruments, proposing alternatives to language and signs. The signal registered brings us back to the question of the natural magician. What does the instrument tell us? Does its voice reveal some secret of nature? In natural magic, words and things are closely linked: words are more than arbitrary symbols for something; they also contain an occult meaning, and one can learn about the thing through the word.

I would like to write/record/produce a visual essay operating through allegory and analogy with hidden connections. Both the words and the instruments at CERN point to the hidden essences of things. They are a grammatical instrument that convokes.

What do you expect from your residency and your exchanges with the scientific community?

I expect to experiment with paradigms and systems of translating from the dimension of the invisible or inaudible. The existence of expressive matter has deeply symbolic meanings and depth—eloquent, emotional, charged particles. Perception and faith are intertwined in a dialectic of presence and absence so that sense arises in the perceptual field rather than in subjectivity. So, I will be looking for conversations from the perceptual imaginary, where the possibility of interpretation can wonder us.

Your practice brings an understanding of borders from many different fields of knowledge and produces several outputs, from films and installations to sound and writing. Could you tell us about your creative process?

I start from curiosity, finding things that amaze me and weaving concepts together. There is a fundamental part of empirical research with no order or rigour. Then, my creative process is marked by an oscillation of thought between materiality and abstraction. In its development, the ideas move like a pendulum between their mental and physical forms. All artifacts are vessels of meaning existing on a scale that extends from the most abstract to the most concrete.

The outcome of that research materialises in many ways, mostly in a group of works. It is important that the material has a conceptual or narrative relationship with the theme itself. I like it when I’m able to find the way the material speaks through its own process.

I believe I learned this freedom of work between disciplines in the city where I “made myself,” Tijuana (Mexico), a border town. Borders are places of constant exchange, of evident, visible interaction, as if combing a pair of hair into a braid. And that is because, in reality, it is the same geography interrupted by a geopolitical imposition. That line is not imaginary but a forceful accumulation of materials and politics translated into a series of gestures to continue being the same territory.

Also, I like to work on in-site specific projects. I dig into the history and identity of a building, a town, or a culture. I then focus on looking for connections and intersections between different identities, cultures, publics, platforms, disciplines, institutions, and ways of interpreting and living in the world.

My creative process is marked by an oscillation of thought between materiality and abstraction. In its development, the ideas move like a pendulum between their mental and physical forms

How would you describe the relationship between your artistic practice and the ‘moment of invention’ in the history of science and technology?

My interest in technology has to do with wonder, like in those times when technology was understood as a magical phenomenon. It has always been linked to the natural. It has evolved to explain ourselves and our world. I am fascinated by exploring the moment of invention, understanding it as one episode of an extraordinary story that has been evolving in languages, approaches, philosophical intentions, and meanings. I am also intrigued by how visions of scientific and technological progress carry implicit ideas about collective futures, public expectations, and the common good. These ideas are constantly evolving, not just in technological processes but in conceptual meanings.

Many exceptional innovations have not been fully developed, existing only in instructions, drawings, absurd contraptions, unfeasible gadgets, poetic constructions of utopian dreams, censored designs, and so on. I am particularly moved by these rescue (in the sense of finding) and forgotten inventions because of their absurdity, impracticality, or lack of relevance in the particular historical moment they were envisioned. Many of these technologies reveal past concepts of the future that never came to be. Negotiating between the past and the future acceding to the present moment becomes a form of cultural archaeology.

A concrete antecedent could be the Zanfona-Telar, 2015 (Hurdy-Gurdy in Loom). In this piece, a mechanical loom, a musical instrument from the XIV century, and violin-making techniques were integrated into an interactive artwork. Another example is Wooden Trumpets, 2014. The relationships between materials, trades, industry, crafts, functionality, and technology are woven together, connecting acoustic technologies of the XVII century, the mystics of alchemy, pre and post-War radars, ear trumpets, distillation stills, do-it-yourself patterns, pre-industrial tools, and bagpipes. The result was a group of drawings, photographs, cut-outs, scale models and projections, and a series of wooden trumpets. I built them in collaboration with a Scottish master cabinetmaker, and each resulted in different shapes and, therefore, acoustics.

Combinations make invention possible. Combinations are an abundant resource for intertwining and adapting technical inventions, the history of knowledge, the act of making, and the process as an empirical observation, with methods, tools, and modes of work taken from craftsmanship and traditional skills and knowledge. I am interested in applying this archaeology of knowledge to developing a body of work where the intersections of materials and disciplines speak to us about possible connections.

You have previously explored the multiple layers of scientific knowledge in your works Cónica, 2016 and Five Variations of Phonic Circumstances and a Pause, 2012. How do you envision the creation of knowledge in scientific environments?

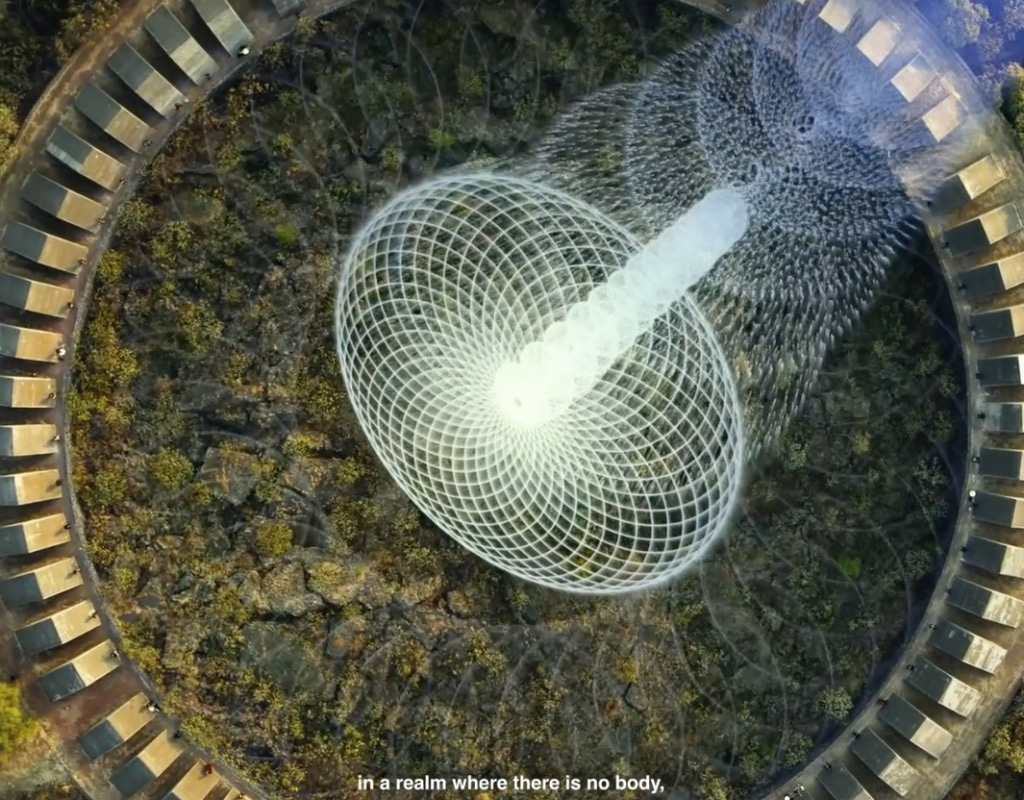

It is great that you mentioned these two projects. Cónica is based on the cosmogony and knowledge of the Kogi Indigenous People from Tairona, Colombia; Cinco Variaciones is an exploration and translation of technological citations inspired by Athanasius Kircher, the most extraordinary polymath in European knowledge.

My relationship with knowledge and science happens from a non-objective approach—a bridge through subjectivity where the notion of wonder magnifies its perspective. Specifically, with science, I have an ontological understanding of the primordial questions, a metaphysical form of extending my mental space and consciousness, exercising empirical observation based on the polysynthetic metaphysics of nature. This empirical approach turned out to be a condition for my creativity, based on joy, pleasure, and phenomenological knowledge—an experimental exercise of chance and intuition.

My work has involved instruments from the natural magic tradition to technological imaginaries, which enchant us or substitute one sense for another (synesthesia)

I took heads and trumpets, magic mirrors, automata, and Aeolian harps, all invented by Athanasius Kircher when the distinction between science, magic, and belief had not yet been established, and it was thought that the movement of the stars was governed by divine laws. Kircher has been a constant reference in my work ever since 2012’s Five Variations of Phonic Circumstances and a Pause, when, in long conversations with Karla Jasso—the curator of that exhibition at Laboratorio Arte Alameda—I came to understand him as one of the cornerstones of the archaeology of the media.

Instruments from the natural magic tradition continued to be invented through the 19th century, although they stopped being called magical. Natural magic never really disappeared but was instead subsumed into new categories, such as entertainment and natural science. We tend not to think of magic as a practical art—certainly not in a useful sense—but many of its objectives, such as creating realistic images without substance, communicating instantaneously across the world, imitating and preserving the human voice, revealing hidden sources of power and travelling under the sea and through the air are mundane technologies today.

Instruments and devices have a life of their own. They often determine theory by establishing what is possible, broadly defining what can be thought. The study of these apparently tangential inventions and instruments can reveal connections that would otherwise be invisible. The peculiar thing about these instruments is their ability to close the gap between the highly scientific and the non-scientific. In this case, the margins indicate shadows – the limits of scientific legitimacy. But the margins are also places of contact and connection between different themes and entities.

I am not just interested in the artifact itself but also in its potential as a conceptual instrument. I am interested in understanding the production of knowledge, in which alchemy, music theory, science, philosophy, theology, astrology, and mathematics all combine, with no trace of hierarchy between them. I am interested in the relationship between human and mechanical forms of power and nature. I am interested in the possibility of using mechanical means to extend or improve what could be achieved by human labour or effort.

I am interested in understanding the production of knowledge, in which alchemy, music theory, science, philosophy, theology, astrology, and mathematics all combine, with no trace of hierarchy between them.

Both scientific explanations and oral histories are products of historical circumstances and cultural context and are subject to controls that ensure accuracy. What role do storytelling and narratives play in your practice?

I came from the narrative. I studied literature, and for a while, I thought I would become a writer. In my work, a line crosses all my practices: a line of words, narrative structures, and language. I am seduced by the materiality that arises through storytelling. Knowing how to tell a story is the most important tool for communicating with the audience, with the listeners, and with the experimenters—finding ways to provoke the other through language.

Storytellers hone their language skills and develop effective communication styles that embrace sensitivity and insight. They draw virtual pictures in their audiences’ minds that enable them to explain complex ideas in ways that make them understandable and accessible.

How to explain paradigms as a storyteller? The act of narration itself is highly self-conscious, constantly seeking ways to redefine realities, to resignify micro-constellations

The singularity of each concrete situation and the authenticity of the specific, contextual meanings intensify the empathic perception of intimacy, fragility, and micro-history. This enhances our sensitivity to diversities, anthropological multiplicity, and the singularity of lived realities. Fictionalizing is a profoundly poetic act: understanding through the storytelling of an unfolding story. It is a metaphor for each named thing. The particle of material that tells and narrates is language. So language is matter.

Storytelling and oral histories are important in this project. Oral history enables people to share their stories in their own words, with their own voices, through their own understanding of what happened and why, in both traditional knowledge and the language of science.

How would you describe the relationship between quantum physics and science fiction narratives? How can we explore these entanglements through art?

There is a beautiful way to describe those entanglements in what Donna Haraway calls SF. SF takes the initials of Science Fact, Science Fiction, and Speculative Fabulations to refer to an area of flexibility to understand, through critical theory, intersectional views represented by speculative feminism, the creative possibilities of science fiction, and the accuracy of science facts. This flexible knowledge effectively addresses the hybridity of experimental materiality and fiction and opens up the door for unexpected transdisciplinary outcomes.

Speculative fiction is a tool for telling possible stories. Technological tools allow for the visualization of possible futures, the projection of possible empathic scenarios, and the raising of consciousness about environmental issues. This healing evocation seeks to stimulate the empathy necessary in the arts of living on a damaged planet.

Both the perception of the nature of things and the apprehension of reality have varied through the centuries, but in moments of fundamental revision, the poetic sight and the scientific approach to capturing the essence of “being” are increasingly closely related.

We are all time travellers, moving from fact to fiction at a rate of sixty seconds per minute. Change is continuous. It seems that we are inventing the world faster than ever before, operating in the space between abstraction and speculation to challenge the ideological and cultural ideas about science. I imagine myself exploring these entanglements making visible things that we rarely see…beauty particles.

Metaphors are bridges between our abstract thought and our experience of the worldly. Allusions to our material world bring such abstractions to a plane of understanding. In a probabilistic universe of uncertainties like the one described by quantum physics, chaos, and randomness rule the most intimate level of cosmic matter. At this fundamental level of existence, metaphors trace meanings over any gap.

A metaphor is also a new start. A möbius strip. A new start that is paradoxical without beginning or end, inside or outside, front or back. And endless fluid space.