- Tags

- Art commissions

- Author

- Ana Prendes

Three years after its premiere in Art Basel, we spoke to Ruth Jarman and Joe Gerhardt about the evolution of HALO, their research at CERN deconstructing science as a process, and their interest in looking out for the unknown

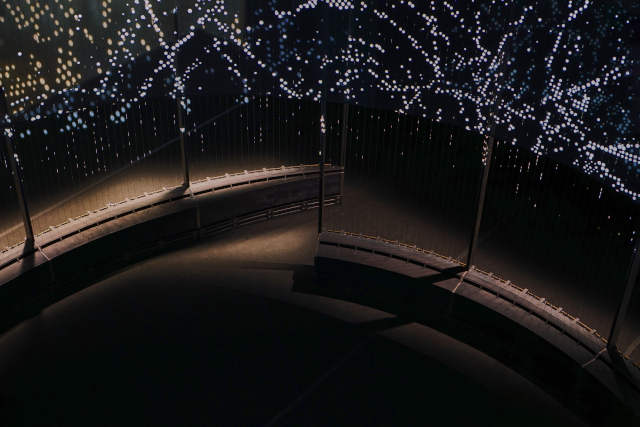

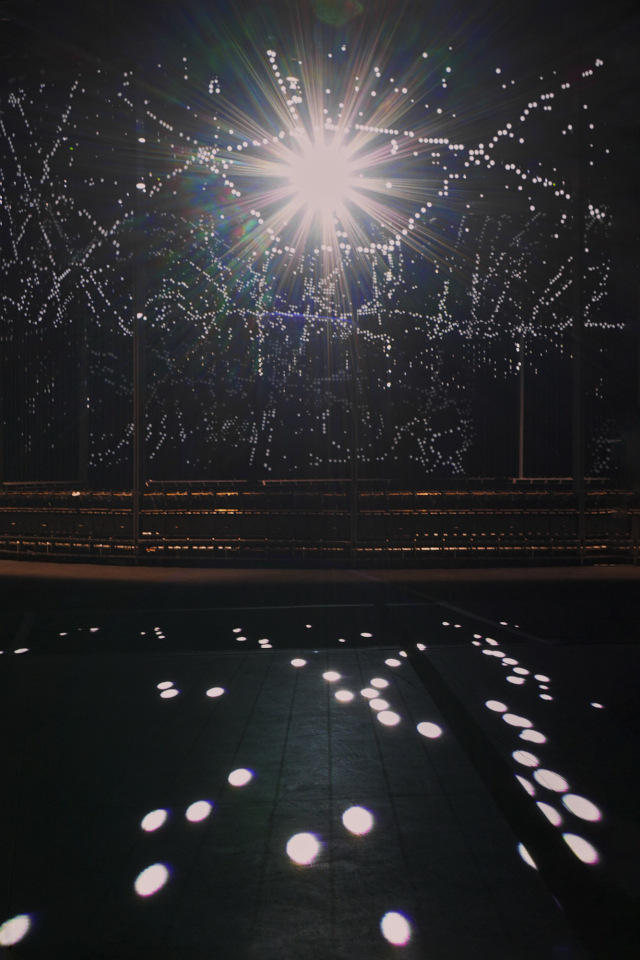

By entering into a blackened theatre in the round, the viewer encounters the ten-metre-wide cylindrical shape structure. It houses a 360-degree screen surrounded by 384 vertical piano strings standing four metres tall. The monumental immersive work invites the visitor to physically experience a particle physics event, transcending its scientific context and reflecting on the technological mediation of nature.

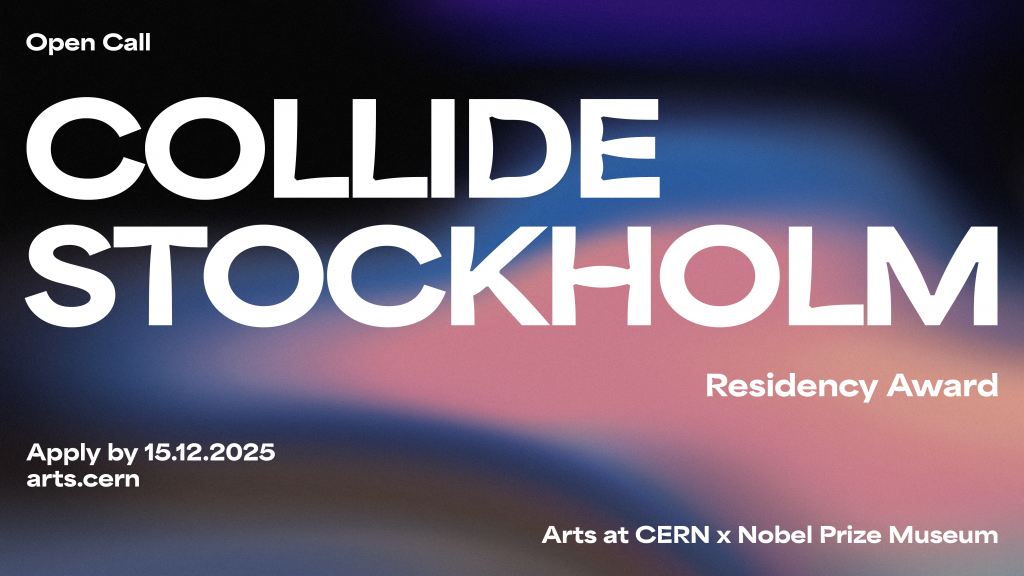

HALO is an Audemars Piguet Art Commission curated by head of Arts at CERN, Mónica Bello. Among five nominated artists by Bello, Semiconductor was selected and supported to develop their proposal in connection with the scientific community at CERN. The animated projection resulted from the translation of raw data from the ATLAS Experiment into the 3D space. Each data point corresponds to a particle ejected from proton collisions that interacted with the ATLAS Transition Radiation Tracker – one of the tracking subsystems of the ATLAS Inner Detector– which also reminisces HALO’s architecture. As the light points appear on the screen, they trigger small hammers that hit the piano wires. The resulting synchronised soundscape builds up gradually through the artwork until the projection finishes and the hammers stop, leaving a humming noise that completes the sensory burden.

Gerhardt explained that they aimed to create an experience where people can feel as close as possible to the event of what’s happening at CERN while creating a human frame of reference. The installation dimensions and the slowed-down data speed, by human perception, envelop the audience in the work. The artists were intrigued by the complexity of data, which reflects nature and the technological lens imposed by humans to interpret it.

Could you tell us about the evolution of HALO since its premiere at Art Basel in 2018?

Joe Gerhardt: We’ve developed quite a lot sonically. In Basel, considering its complexity, it took quite a short time frame to make it. This time, the sound has nicer resonances and is more subtle.

Ruth Jarman: We have made many modifications to the electronics and mechanics. It’s really nice to have been able to evolve it as an artwork. It feels like a huge achievement to show HALO at this moment, considering we’re still emerging from the pandemic, the kind of collaboration it takes to bring it to the venue, and what it entails to allow the public access to it. We were meant to be exhibiting at this time last year, and we weren’t sure whether it would even happen.

How is this new exhibition space at the Attenborough Centre, amidst a university campus, compared to its original setting in an art fair?

JG: This is, in a way, where the story of HALO started. Before we went to CERN, the previous director of Attenborough Centre for Creative Arts, Sally Jane Norman, introduced us to the physics department where Antonella [De Santo], Professor of physics, put us in touch with Sussex Fellow Mark Sutton, who was based at CERN. Mark was instrumental in HALO coming to fruition. It started from those discussions in this space five years ago. It’s come full circling in that sense; this is a circular building; it’s a circular sculpture (laugh).

RJ: We also live in Brighton, and it’s showing as part of the Brighton Festival. This brings quite different audiences from when we exhibited it at Art Basel; it opens it up to a much broader public who engage with the arts and culture. But, as you said, it’s also on the university campus. Part of what we’re doing here is engaging with the music department at Sussex University. Many musicians work across music and technology, and they’re coming to spend a day with HALO to see how they might perform with it as a musical instrument or alongside it, so we’re developing those kinds of relationships.

We’re interested in that data not in the scientific context but what it is as a material and what it says to us as humans

JG: It’s becoming an instrument and a stage at the same time. We want to think about HALO from every different angle, which is kind of like what happens at CERN. It’s not just how that matter affects everything but how you can understand it from different perspectives.

You’ve worked with raw scientific data in other works, such as Earthworks (2016) and 20Hz (2011). What draws you to raw data?

RJ: We work with scientific data – that could be numbers, points in space like here, or images – as close to how it comes out of the instrument as possible before having any layers of information added or removed. If we’re talking about an event display, you end up with this very colourful diagram integrated with the instrument and all these lines and squares. The scientists can read that information in a very visual way. To get to that point from the raw data, many things have been removed or added so it becomes readable in a scientific context. We’re interested in that data, not in the scientific context but in what it is as a material and what it says to us as humans.

JG: Scientists try to remove all the noise to focus on results. But that noise is part of nature, the texture, and the story of what’s really going on there. For example, NASA images are artificially colourised and are composed of multiple photographs. But the grainy black and white photos they start from are to us just as beautiful, and they have more of the story. Here, we’re using minimum bias data, which scientists collect before it’s filtered or changed. For us, the nature of what is raw is a real thing rather than just aesthetics.

At the same time, you are seeking to convey the ATLAS experiment that is creating and collecting this data and the human framework behind the technology.

RJ: Yes, we’re interested in how you can look at the data. There’s a certain complexity in it, which suggests nature, but there’s also a structure to the form it takes, how it exists, and you get an idea of man and technology reading that nature, so we’re trying to play those off against each other. When you go into the space, you’re experiencing those things. You’re not thinking of them in a scientific context; we’re interested in what that becomes, what it then tells us about nature and how we respond to that.

How would you describe HALO’s immersive experience?

JG: We were interested in creating an experience where people can get as close as possible to the event of what’s happening at CERN, creating a human frame of reference. For example, a scale and a speed that your mind can relate to. At CERN, they collect a billion events a second and record hundreds of thousands of them; the events happen close to the speed of light. We slow them down to experience them in a human time frame. These machines are also cathedral-size; we’ve scaled them down so they place you at a point where you can imagine being the particle, placing yourself in relationship to the experiment.

We want to transcend the data. HALO becomes an experience similar to a natural phenomenon; you don’t need to know anything about science to engage with it

RJ: At the same time, we also want to transcend the data, so it almost becomes like how you might experience a natural phenomenon. You don’t need to know anything about the science to experience HALO; it is an experience in its own right. As Joe said, when we work with these different parameters, it is about how we as humans can process and perceive information. We work specifically with that, so it’s like experiencing the sublime.

JG: We could have sonified it, where you take all the data and associate each point with a note on the musical scale, for example, but then you have a cultural anthropomorphisation where you introduce another layer of human language. With HALO, we hear the natural resonance of the sculpture; it’s still raw, and you can build your narrative from it.

During your residencies at CERN, you also examined the processes and the tools of scientific research, as you explored in your film The View from Nowhere. Can you speak about your encounters with theoretical physicists?

RJ: We interviewed many theorists and deconstructed science as a process with them. In The View from Nowhere, we play the theory off against the experimental side and the practicalities of doing experiments. You see that what the theorists are doing is really playful and that they’re very creative with how they approach their science, and they have to be. On the opposite side, you have physical limitations. We spent a lot of time filming in the large magnet facility and the CERN workshop, where they make many prototypes for the instruments. A fact that always interested me about CERN is that the size of these magnets depends on the longest object you could drive along European roads. They are made somewhere else, and then they had to be driven to CERN. So they are limited by scale in many ways. In The View from Nowhere, you get this sense of them playing off of each other.

How would you describe your practice within the vast space between artistic and scientific research?

JG: We’re ultimately interested in nature and looking out for the unknown. As soon as you start looking at the unknown, you have to use technology and scientific ideas to explore those areas, so it’s simply just the medium to be able to look at nature. Our relationship with scientists is more that we experiment on them (laugh).

To look at the unknown, you have to use the ideas and tools of technology and science

What’s next for Semiconductor?

JG: We’re working with some scientists at Dundee University who are looking at planetary formation in the universe. We’re working with some of their data and trying to get our heads around that. We’re also experimenting with HALO as a sonic instrument.

JG: We hope to go back to CERN soon. We’d like to show HALO there.

RJ: While we were there, we developed many ideas for projects. We’re interested in so many different strands of research, so I know there are many loose threads that we need to revisit.

HALO is on view at the Attenborough Centre for the Creative Arts, Brighton, UK, until 4 June 2021.