- Author

- Johanna Bruckner

Following her residency at CERN, Johanna Bruckner discusses her artistic research on interfaces, how AI-generated images reshape our interpretation of the world, and the interplay between affect and machine learning as a transformative aesthetic

A few months ago, I started my residency with Arts at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, one of the world’s most renowned centres for scientific research. I was selected for the Connect residency programme, in partnership with the Swiss Arts Council Pro Helvetia. I would like to share my initial experiences of this environment in the context of my dissertation’s aesthetic approach and research focus.

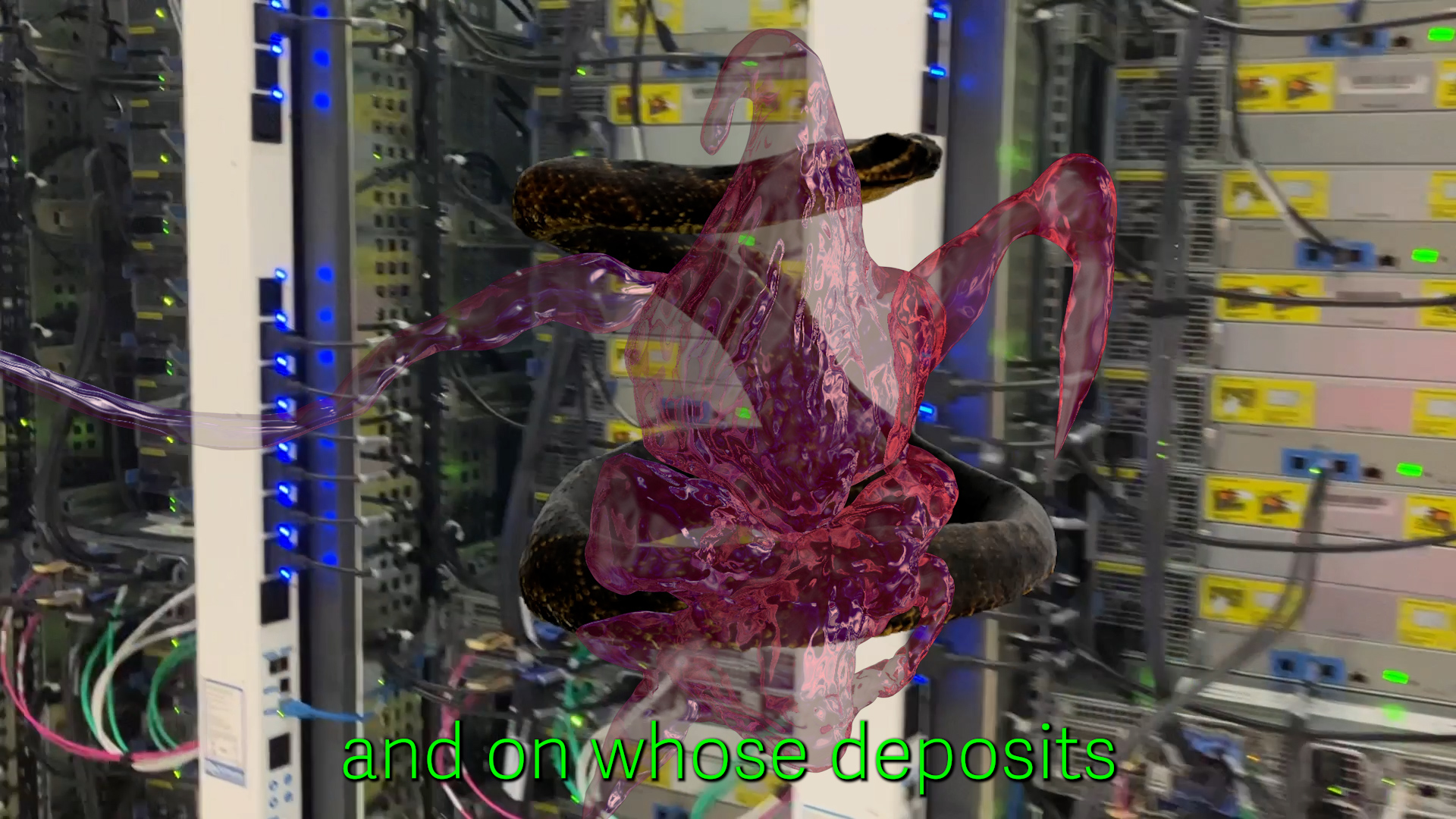

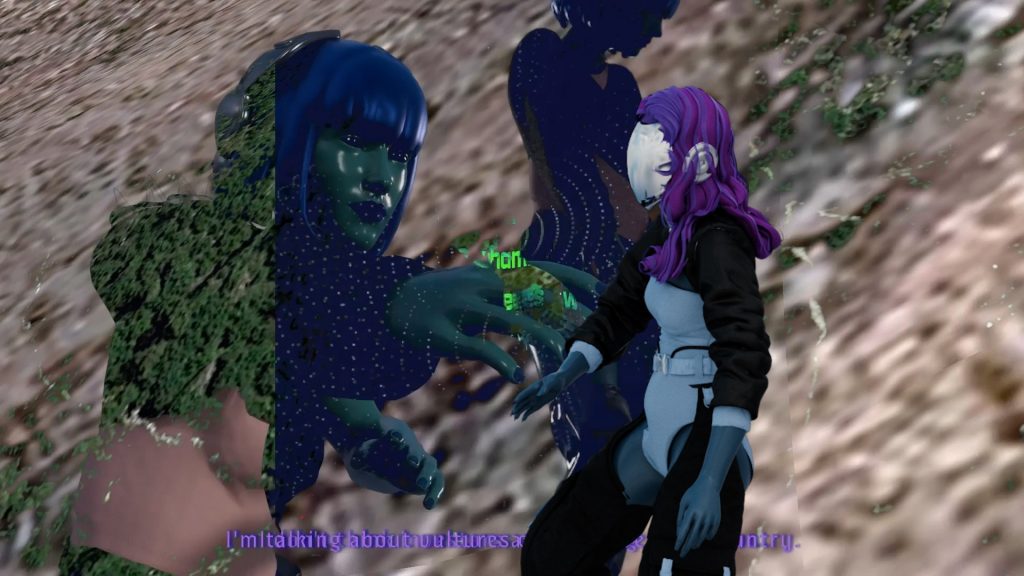

Here, you can see the visual material I have produced as part of my ongoing research on interfaces, which focuses on both the relationship between affect and machine learning as an alienating and transformative aesthetic. My project explores the influence of AI on moments of desire and its opportunities for agencies. Using AI and social media footage, I produced a video that examines responses to user representations in failed and ambiguous encounters with AI, asking how images of machine learning change our understanding of the world. How do people view these images and their (failed) promises, and how are changes in imaging being articulated, distributed, and circulated?

CERN seemed to be an interface of colliding experiences and knowledge in transition

I arrived at CERN on a rainy day. A registration card at the entrance granted me access to this high-security enclave. Once inside, orientation was difficult; I steered a course through streets consisting of block buildings, some reminding me of old factories and warehouses. I couldn’t imagine what, if anything, might be inside. But it also occurred to me that CERN seemed to be an interface of colliding experiences and knowledge in transition, like a junction between the outside world and the knowledge within. Scientists come and go regularly to work on experiments.

A theoretical physicist introduced me to his field of study: inside the colliders, which are specially constructed rings under the earth, many kilometres in length, particles collide at nearly the speed of light, either splitting into smaller parts or creating new particles. The physicist tells me that scientists at CERN study the more “interesting and new particles”, those that are unknown, unfamiliar to physics, or seemingly do not abide by the laws of physics. These experiments, he told me, help us to understand the behaviour of such particles and provide insights into how their interaction with other particles could lead to different relationships between machine and medium, depending on whether their charge is negative, positive, or neutral.

Using AI and social media footage, the video examines responses to user representations in failed and ambiguous encounters with AI

The results form a kind of code that allows systems to interact repeatedly and to be quantified and computed, which helps in creating interfaces for data transportation and translation. The stranger the behaviour of the particles, the more complex the interfacial interactions. The greater the number of unknown particles, the more complex it is to translate them into knowledge, and the more extensive the scope for imagining realities beyond binary concepts.

Data alone does not provide us with a representative view of the world. It is often cloudy, full of errors, hidden ideas, and biases. It requires the use of various interfaces to become meaningful. Solutions are often hidden inside the black boxes of interface development, which generate unclear output (Stalder 2023). In my research, I assume that interfaces are inherently ambiguous, that is, full of meaning that needs to be interpreted in an ocean of possibilities. I consider this ambiguity a creative opportunity and approach data as an open concept.

Understanding technical machines as social, cultural, and affective ones allows me to translate this complexity into agential and corporeal forms (ibid.). My ongoing research is therefore guided by the following questions: What kinds of data/knowledge collisions are enabled by the interface, and how can they be translated, interpreted, and embodied?

How can artistic strategies bring to light the complexity and interconnectedness of interfaces?

A postdoctoral researcher guided me through the halls of CERN’s Antimatter Factory, where large-scale experiments are conducted. She told me about antimatter, forms of dark matter that do not obey the laws of physics as they apply to gravitational force and whose interactions with matter are rather unclear. Neutrinos are recently observed particles in quantum physics that have been used to explore little-known behaviours such as teleportation, the process by which particles behave in the same way in different locations simultaneously. This process is exemplified in an experiment that I witnessed, which took the form of an extra-dimensional yellow-lit cage filled with liquid gold. This set-up provided the appropriate conditions for particles to interact in such ways that we could describe and characterise them as affective and sensory, which therefore precluded any calculations.

As a blueprint for affective computing, this study draws on an interdisciplinary interest in the nonverbal, often trans-subjective, and sometimes unconscious dimensions of embodied experience and knowledge, including feeling, sensation, and attention. Pioneered by Rosalind Picard in the early 1990s, the turn to affect in AI research has helped to advance the knowledge, understanding, and development of systems to sense, recognise, categorise, and react to human emotion (Lee 2016, 18). What remains unresolved, and of particular interest to me, are the machine learning techniques that have not yet been developed to detect non-standard situations in the monitoring of the operator parameters. What characterises the non-standard situation here, and what do these techniques tell us? How do they represent the world and provide feedback?

Speculation and uncertainty are the primary guiding principles for most scientists and are inherent in their research and interpretation of reality

I reflect on the threshold between imagination, affirmation, and frustration of technology as an interface of a visual, embodied experience

Speculation and uncertainty are the primary guiding principles for most scientists and are inherent in their research and interpretation of reality. However, humans maintain an ambiguous relationship with increasingly autonomous technological tools and their translation into virtual images. My practice at CERN is thus concerned with the interpretation of data through interfaces and the impact of their ambiguities on public discourse: How can data interfaces be used to explore, expose, and make use of ambiguity? How can artistic practice inform new frameworks for understanding the ambiguities inherent in data interfaces? These questions guide my investigations, in which I view each step along the data science route as an opportunity to create different data-driven narratives and new ways of engaging with them.

To conclude, I am interested in the alienating potential of the “in-betweens” of interfaces that allow possibilities to co-exist, and wish to bestow corporeal agency to the liminal space of a non-narrated, improbable world. My work includes a queer-feminist contextualization of algorithmic developments and data science. I try to broaden the understanding of technology as a cultural and affective agent and focus on its performative aspects. I reflect on the fragile threshold between imagination, affirmation, and the frustration of technology as an interface of a visual, embodied experience, asking how science-led transformations can challenge how people interpret the world beyond binary regimes of agency, gender, and utopia

Bibliography

Lee, W., Norman, M., 2016, Affective computing as complex systems science“, Procedia Computer Science 95, 18–23. Stalder, F. (et. al.), 2023, Latent Spaces, Zurich University of the Arts, see https://latentspaces.zhdk.ch/About. Last accessed on 11/01/2024.